Biography

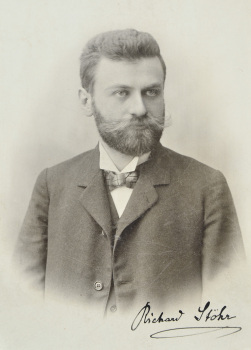

Richard Stöhr (Stoehr): 1874-1967

Life from 1874 to 1938

Richard Stöhr (1874–1967) was born Richard Stern in Vienna in the same year as Arnold Schoenberg. His Jewish parents were originally from Hungary. His father, Samuel Stern, was a professor of medicine at the University of Vienna. His mother, Mathilde, was the sister of Heinrich Porges, one of Richard Wagner’s closest associates. Stöhr first obtained an M.D. degree (1898) from the University of Vienna but immediately entered the Vienna Academy of Music (now known as the University of Music and the Performing Arts) as a composition student of Robert Fuchs. At this time he also changed his name from Stern to Stöhr and converted to Christianity.

In the annual Summary of his Diary from 1898 he wrote: “This was the year the big change occurred. Herewith I have sealed the fate of my future life. Now I am a musician and I carry this responsibility seriously, consciously and without regret. At the same time came the actual change of my name to “Stöhr,” on which I had decided already in the summer. It was just the right time for this and I am glad I didn’t miss it. I am certain that in the future advantages will come from this for me.”

He was also helped and encouraged in his musical studies by Heinrich Porges, of whom he wrote the following in the annual Diary Summary of 1899: “Uncle Heinrich stayed with us as guest in the middle of September. His brief presence gave me enormous advantages, especially the ability of getting free tickets, even orchestra seats at the opera. He even introduced me to Mahler and in general did everything for me that I wished and what could only be an advantage for me. His opinion about my musical ability surprised me particularly. He emphasized my ability in counterpoint, where he is probably right.”

After completing his studies with Fuchs and earning a Ph.D. in Music (1903) he first worked at the Academy as a rehearsal pianist and chamber music coach. Soon he was teaching courses in theory, composition and the history of music. Upon Fuchs’ retirement in 1911 Stöhr took over his most advanced courses became a full professor at the Academy in 1915. That year he was called up to serve as a physician in the Austrian army and while serving in a hospital in the suburbs of Vienna was able to live at home and continue teaching at the Academy. His first book on harmony appeared in 1906 and his early success as both author and composer is indicated in the diary summary for 1909: “Of even greater importance for me was the success of my “Harmonielehre”, of which the first edition was already sold out in June and has therefore already appeared in the second edition. The critiques of this work were extremely positive from all sides. The performances of my compositions reached such frequency this season that some newspapers even commented that this was inappropriate.”

Between the world wars Stöhr continued his prolific work as composer, author and teacher. His eventual output as a composer includes seven symphonies, two operas, choral music, 150 lieder, 15 violin sonatas, at least a dozen other major chamber works and solo piano music. His literary output includes at least half a dozen books and numerous articles.

In 1923 Richard Stöhr was finally able to marry his longtime companion, Marie (Mitzi) Eitler. They resided at 14 Karolinengasse near the Belvedere Palace in Vienna. They had three children in the 1920’s: Richard, Heinrich (who died in a drowning accident while still a toddler) and Hedwig (Hedi). Although Stöhr’s position at the Academy was secure during the difficult economic times of the 1920’s, three bank failures in the 20’s and 30’s wiped out a considerable amount of his savings and investments.

The following is an excerpt from a personal reminiscence of Stöhr’s Vienna years by former student Hedy Kempny:

During the 1930s I was a student of Dr. Richard Stöhr at the Academy of Music in Vienna. He was my teacher of History of Music and Harmony. All of us women students were very fond of him. Not only was he a very handsome man, but we also found his teaching fascinating. Soon we followed him wherever he went; to concerts or when he was invited into private homes, where musicians dared to make us acquainted with a new kind of music by composers such as Richard Strauss, Gustav Mahler, Arnold Schoenberg, Alban Berg, Erich Korngold and many others. Stöhr was still Conservative, but open minded about the new era, which soon hypnotized us.

Stöhr lived in a typical “old Vienna” home with two pianos in the huge music room. On the walls there were photos of composers and famous people he knew in various countries, as well as snapshots of students and friends. Every two weeks he had a “musical evening” to which anyone who wanted to come was invited. We would gather at about seven o’clock and bring along friends who wanted to meet Dr. Stöhr. It was quite informal, and sometimes he came later and found the apartment crowded by thirty or more people. Many of us brought food such as cheese, sausages, salads, fruit or cakes. We deposited these in the kitchen and after a short time we gathered in the living room, where all the goodies were displayed on the table and we helped ourselves.

Richard Stöhr at the piano in his music salon, ca. 1925.

But soon Stöhr got up and went to the music room and sat at the piano. He called out “Pifferl”, his pet name for his wife Mitzi, and she came quickly and stood behind him and massaged his head while he played. Indeed this was strange, but we knew of this eccentric behavior of his and nobody minded. He had other strange habits. For instance when he was invited to someone’s house he brought out of a pocket a folding coat hanger for his coat. Many times all kinds of famous people attended these gatherings without fanfare. For instance Bruno Walter, Felix Weingartner, Korngold and other musicians. Sometimes Stöhr’s beautiful Lieder were interpreted by opera singers. Later in the evening there were discussions, not only about music, but also about what was new and exciting in Vienna. Stöhr talked and listened and argued. He was versed in every field and subject. The discussions were most interesting and stimulating. Stöhr’s heart and mind stayed young and flexible. He gave help and advice to us younger ones who asked for it. What a wise man he was!

Life from 1938-1967

Following the Anschluss in March 1938 Stöhr was immediately identified by Nazi officials as a Jew and fired from his position at the Academy of Music. The University of Music and the Performing Arts provides the following account of what happened to Jewish faculty members in the aftermath of the Anschuss:

-

THE ACADEMY UNDER NAZI RULE (1938 – 1945)

-

Immediately after German troops marched into Austria on 13 March [1938], an SS intelligence unit was housed in the state Academy. Over the next few days, the interim director suspended eleven teachers who, under the Nuremberg Race Laws, did not have the “right” to swear allegiance to Hitler due to their Jewish extraction. A list of cuts dated May 1938 contains the names of 23 teachers who were no longer to be employed on the grounds of their race. Several of the teachers were allowed to emigrate. The fate of several other teachers is unknown.

-

On 31 May, the director also terminated all existing contracts, most of which were renewable annually. This step gave the authorities the chance to examine the ancestry and political allegiance of all the teachers. Those who were not given a new contract in the autumn were not considered to have been injured and were therefore not entitled to compensation. All in all, these dismissals for racial, political or even personal reasons affected almost fifty percent of teachers.

In February 1939 Richard Stöhr emigrated to the United States. Had he not left Vienna he probably would have shared the fate of his sister Hedwig, who was rounded up by the Nazis in 1941 and who died in a transit camp in Poland in 1942. From this time until the end of his life he used the alternate spelling of his name: Stoehr. He was hired personally by Mrs. Mary Bok Curtis to come to the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia initially as music librarian and subsequently to teach courses in theory and composition. Stoehr was also hired to translate part of the Burrell Collection of the Letters of Richard Wagner (published by MacMillan in 1950). Stoehr’s family spent the war years in four different countries: Stoehr in the US, his wife Marie stayed in Vienna, Richard in Sweden and Hedi (via the Kindertransport) in England. They were gradually reunited in Sweden and the US in 1946-47.

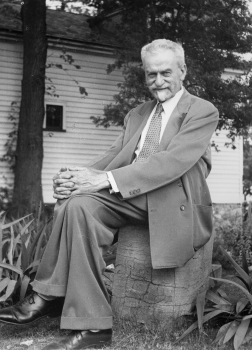

Richard Stoehr at Saint Michael’s College, 24 July 1949.

Curtis downsized their faculty in 1941 due to the war and Stoehr was let go from his position there. He quickly found another position at Saint Michael’s College in Winooski Park (now Colchester), Vermont near Burlington. There he taught German language as well as music courses. The College was not able to pay a full time salary, so Stoehr was assisted by at least one refugee aid organization. Stoehr continued to compose prolifically during his years in the U.S. in all major classical genres except opera. While virtually all of his compositions prior to 1939 were published by reputable firms including Universal-Edition, none of the numerous compositions from his U.S. years were ever published. Stoehr retired from teaching in 1950 but continued to live at Saint Michael’s for several more years. During his 50 year career as a teacher his students numbered in the thousands and included Herbert von Karajan, Erich Leinsdorf, Rudolf Serkin, Samuel Barber, Leonard Bernstein and Marlene Dietrich. Richard Stoehr died in December, 1967 in Montpelier, Vermont and is buried in Merrill Cemetery in Colchester.